Internees: Male

Send me the following: 2 packs of playing cards, milk of magnesia, California ripe olives, Yardley Solidified Brillatine, couple lbs. sliced cooked ham, ½ gallon olive oil if you can get it, vinegar (some of our friends here receive quite a lot of lettuce and other vegetables so we use quite a bit of oil). Also send 2 pairs of winter underwear, 2 pairs of mitts (not gloves). Do not send any more apple juice we do not like. Can you send honey dew? That’s all for now. … P.S. Do not forget 50 packages of cigarettes.

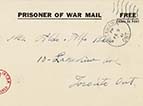

Internee Leo Mascioli in a letter to his son Dan, courtesy of Paula Mascioli, Columbus Centre Collection

Internees were sent to camp by train. On arrival, they handed over any personal possessions and received two sets of summer and winter camp clothing. This included a winter jacket, work boots, wool socks, undergarments, and one light and one heavy cap. The clothing was blue with the exception of a large red circle on the back of each shirt and jacket. These circles served as a sniper target in case of an attempted escape. An internee’s camp pants had a red stripe that ran down the pant leg from the hip to the bottom of the leg. A red stripe was also present on the caps provided to internees. The stripe began at the back of the cap and continued to the edge of the visor.

After an internee had changed into his camp uniform, he appeared before the camp commandant to go over the camp rules. Each group (German, Italian, anti-fascist) within the camp had a spokesperson, who was recognized in this role by the Ministry of Justice in Ottawa, and who was present during the first meeting with the commandant. The spokesperson was the contact between internees and the camp commandant. He gave the commandant’s orders to the internees, held regular meetings with the barracks leaders, and distributed the internees’ mail. In Petawawa and Fredericton, Montreal lawyer Mario Lattoni performed this role. Another lawyer, Vancouver’s Ennio Fabri, was the spokesperson in Kananaskis.

Life at the camp was based on military discipline and was heavily regimented. Internees saluted all officers of the rank of sergeant-major and higher, referring to them as “Sir.”

Work

The internees included labourers, tailors, contractors, priests, doctors, lawyers as well as convicted and suspected criminals.

Internees who were under sixty years old did manual labour or vocational work. Manual labour included road repair, chopping wood used for cooking and heating, and maintaining the camp. Vocational work involved trade or professional tasks. For instance Dominic Nardocchio, a cobbler by trade, repaired the boots of internees and camp guards; and Dr. Luigi Pancaro worked in Petawawa’s infirmary.

Others worked where they were needed. For instance, the camp kitchen was staffed by chefs or cooks as well as others with no experience in food preparation. Internees did not work every day.

Internees were paid twenty-five cents for a day’s work. This money could be used to purchase items from the camp canteen such as toothpaste and cigarettes.

Food

Internees were given three meals each day. Breakfast included coffee, milk, oatmeal, bacon, fruit juice and eggs. Lunch could feature soup, meat and vegetables, and omelettes. Dinners alternated between meat or fish, with vegetables and pasta. Depending on the season, internees also received apples or a salad. Bread was included with all meals. Internees also grew their own food in vegetable gardens.

Living Quarters

Internment camp barracks were wooden, single-storey structures which ranged in size depending on the camp. Each Kananaskis barrack housed 12 internees while those at Petawawa contained 60 internees. The barracks at Fredericton were the largest and had room for 160 men.

The barracks at Petawawa and Fredericton had toilets, sinks, showers, and electric lighting. Oil lamps were used for lighting in the Kananaskis huts, before electricity was introduced, but they lacked plumbing. A common latrine was used by internees at this camp. Regardless of location, the barracks contained wooden tables and benches, and a woodstove for heating in winter. Internees slept on bunk beds with a thin mattress.

Every barrack was assigned a number and was represented by an appointed barrack leader who acted as liaison with the camp spokesperson. Internees had to keep their barracks clean. Barracks were inspected daily by the camp commandant accompanied by military police and the camp spokesperson.

Barracks were organized along ethnic and political lines. Thus, Italians did not bunk with Germans; fascists did not bunk with anti-fascists.

Recreational Activities

Internees were often lonely and bored. Recreational activities were organized during downtime. They watched films, read, played cards and chess. Sports such as hockey, soccer, baseball, and bocce were popular. Beginning in December 1941, to alleviate the internees’ homesickness at Christmastime, an annual Field Day was held at Petawawa. During this Olympic-styled event, internees competed in a variety of sports.

Internees formed bands and held concerts. Instruments were either paid for by internees or donated. Artists such as Guido Casini and Guido Nincheri did coal sketches of fellow internees. Vincenzo Poggi completed sketches as well as paintings while in camp. Internees also made elaborate wood carvings.

Writing Letters/Receiving Mail

Internees were allowed to write three letters and four postcards per month. The maximum length for letters was twenty-four lines and eight lines for postcards. Exceptions were made for those who ran businesses and had to respond to letters from the Custodian of Enemy Property. All camp letters were read by a censor. Contents deemed inappropriate were blacked out with ink. The same applied to incoming mail. Camp letters that were written in Italian were first translated into English before being read by a censor.

Internees were allowed to receive parcels from family members. These packages were searched thoroughly by camp guards before being distributed. Internees mostly received food and clothing.

Receiving mail was an important occasion for internees. For most, letters were the only contact they had with family. In rare cases, family members travelled to Petawawa for a brief meeting with a husband or father.